Zoned Out: How Urban Planning Perpetuates Sexist Ideals

Cities are - and always have been - designed and built by men. Men dominate the ‘city-making’ professions, from architecture and engineering to politics and planning. As the feminist geographer Jane Darke famously said, “cities are patriarchy written in stone, brick, glass, and concrete,” a quote which time and time again inspires me to examine urban spaces, gender, and privilege.

While this quote can apply to many aspects of city design, in this article, I’d like to focus on the patriarchy through urban zoning, which is the division of cities - either by law or tradition - into municipal areas for living, working, manufacturing, shopping, and playing. Urban planning dates back to antiquity, but contemporary ‘zoning’ emerged during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a result of the Industrial Revolution. Rapid urbanisation caused overcrowding, poverty, and disease, and created a desire to separate the public and private spheres, detaching work from home.

At the same time, the job boom, increasing population wealth, and the Suffragette movement were all increasing women’s autonomy. Many men believed that women entering the public sphere had triggered the city’s problems, and anxieties emerged surrounding the disintegration of the city and the ‘traditional’ family structure. The solution, men decided, was to move women away from the city to keep the female focus on the home. This definition of the city as a masculine area of production and the home as a feminine area of reproduction cemented the origins of contemporary urban zoning.

Garden Cities are the first major implementation of this zoning. Ebenezer Howard pioneered this new (and horribly detrimental) urban planning in his 1902 book ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow’, which called for clusters of interconnected residential developments linked to other municipal zones in the city with roads and train lines. Garden Cities married urban employment with the benefits of country fresh air, privacy, and space. The first two Garden Cities were built during Howard’s lifetime, Letchworth (in 1902), and Welwyn (in 1920). Howard may have envisioned interconnected hubs of paradise, but now Garden Cities are hugely car-reliant commuter towns; green but overwhelmingly uninspiring.

Ebenezer Howard’s concept for garden cities. Architectural Review

Letchworth Garden City. Regina Jeffers

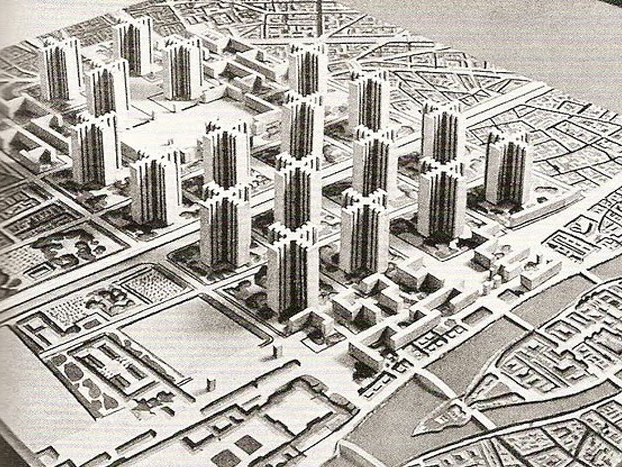

Le Corbusier, the architectural king of the twentieth century, was inspired by Howard’s Garden Cities. Very few of Corbusier’s highly zoned masterplans were built, yet urban planners and architects today are still trying to unpick the chaos that his ideas created. ‘La Ville Radieuse’ (or The Radiant City in English), one of the most influential and controversial urban doctrines of the twentieth century, was his most radical masterplan. It advocated the total demolition of old cities and their replacement with skyscrapers in a zoned metropolis. Large roads would take workers (read: men) from their homes to their downtown offices or the factories outside the city. The city’s ground floor would be given over to cars, and pedestrians would cross the mega-highway on bridges. Buildings would be surrounded by large public parks (Corbusier understood the importance of greenery in a city), but as life would be so heavily divided - with shops and restaurants miles from any houses - these spaces would not have thrived.

We see remnants of ‘Ville Radieuse’ in cities across the globe. Look at Dubai, Santiago, Los Angeles, Shanghai: they all have enormous multi-lane highways bringing cars, noise, pollution, and stress right to the doorstep of where we live and work. Look at the infamous Pruitt-Igoe development in Missouri, Soviet-era housing, contemporary apartment blocks in Hong Kong, and even public housing in New York – row upon row of nearly identical high-rise housing blocks. These Corbusier-inspired cities are not built for people. They are built for cars. They are not built for women or for marginalised communities. They are built for middle-class, middle-aged, non-disabled, car-driving, men.

Model of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse. 99% Invisible

Drawing of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse. Archdaily

But why is this such an issue that cities have been designed for men? Would cities really be so different if women and marginalised communities had their say? Well, the answer is yes. And it all comes down to zoning. The crux of the matter is, that women and marginalised communities use cities in entirely different ways to our typical (male, pale, stale) city-maker. In her 1996 article, ‘The Man Shaped City’ Jane Darke explains that zoning fails because it “compartmentalises activities such as work, leisure, travel and home life, which most women do not separate out in this way,” due to traditional gender roles.

Women are much more likely to perform domestic tasks such as cooking; cleaning; grocery shopping; childcare; and caring for the sick and elderly – than men. In her seminal book ‘Invisible Women’, Caroline Criado-Perez states that women across the globe do 75% more of this unpaid care work than men, meaning they are much more likely do what she terms ‘trip-chaining’. Trip-chaining is the act of completing a series of short, interconnected journeys for unpaid care work, often in combination with paid jobs, like taking the kids to school and running errands on your way to work, then checking in on an elderly relative and buying groceries on your way home. Women are 25% more likely to trip-chain than men, simply due to the imbalance of unpaid care work. And this isn’t just a gender issue: people working multiple jobs or relying on gig-economy work are more likely to trip chain, and these folk are more likely to be in lower-income brackets and or marginalised racial groups.

Trip-chaining involves travelling between different municipal sectors, which is expensive, time-consuming, and is often worsened by inadequate transport systems. And almost every city in the world has a male-focused transport system: arterial roads and metro systems bring people directly into the city centre (work) from the suburbs (home). This benefits men, who, on average, typically have a twice-daily commute at set times and are more likely than women to own and drive a car. Secondary transport systems – usually buses - are typically used more by women. Buses usually have circular rather than arterial routes, and link different areas of a city’s outskirts, which is helpful for trip-chaining. However, buses are chronically underfunded, while governments consistently pour money into arterial transport networks.

This gender imbalance in urban transport is not just a remnant of the past. Transport networks today are also to blame for perpetuating the sexist systems they inherited. Criado-Perez explains that the research done by public transport networks focuses on trips for paid work, education, and leisure, and ignores journeys for unpaid care work. This is eye-wateringly stupid, as unpaid care work is the biggest reason that women travel and contributes an estimated $10 trillion to the global economy. Furthermore, data is rarely collected on pedestrian journeys or trips under a mile long, which are much more likely to be taken by women, due to disproportionate levels of unpaid care work, trip-chaining, and the fact that women are, on average, statistically poorer and therefore more likely to walk. As a result, women are critically underrepresented in travel data. The excuse? Apparently, women’s journeys are too complex to research.

15 Minute City principles. Buro Happold

Trip Chaining. Gender Data

So, what is the answer? Steps to reduce the time and cost of trip-chaining could look like better-connected arterial transport and schemes like hopper fares. But to tackle the issue at the root cause, cities need to desegregate the municipal zones and fully integrate places of work, retail, and leisure into residential areas. This ‘15-minute city’ principle is a clear way to reduce trip-chaining and ensure that women are not systematically disadvantaged based on the layout of their city. It also increases the vibrancy, walkability, and social cohesion of a neighbourhood, while reducing car traffic, encouraging active travel, and allowing green spaces to flourish.

There isn’t a clear downside to 15-minute cities. So, it is strange to see that in recent years, fringe conspiracy theories surrounding the concept have gone mainstream. Adversaries claim that 15-minute cities allow councils to police people’s day-to-day existence through extensive CCTV, monitoring or even controlling how often locals visit shops, use the roads, or leave the neighbourhood. This dystopian nightmare is clearly unfounded; a conspiracy peddled by right-wing social media, fuelled by the trauma of Covid lockdowns, and boosted by celebrities such as Jordan Peterson and even Tory MP Mark Harper.

As the world swings decisively towards fascism, maybe now is not the time for such socialist ideals as having your work, shops, schools and parks at your fingertips. We have bigger fights to fight right now. But I write this in the hope that when the pendulum eventually swings the other way, we have a game plan to finally build the gender-equal city.

Published June 2025.

Adapted from Sexism and the City: An Analysis of Historical and Contemporary Urban Planning and its Effects on Women (Sepha Schindler, 2020).

Key Sources:

Darke, J., 1996. The Man-Shaped City. In: C. Booth, J. Darke, S. Yeandle, eds. Changing Places: Women’s Lives in the City. London: Paul Chapman.

Perez, C.C., 2019. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. London: Chatto & Windus.